The Vaisakhi of 1801 (April 12) marks a watershed moment in the history of Punjab and the Sikhs in particular. It was the day Ranjit Singh chose for his investiture as the Maharaja of Punjab. The ceremony marked the end of years of disorder and foreign rule. For decades, invaders from the northwest had been marauding the northern regions of India, up to Delhi. However, the worst sufferers during this period were the people of Punjab, where efforts were made to exterminate the Sikhs, with bounties placed on their heads. The establishment of the *misls* and their partial unification under Ranjit Singh brought these foreign invasions to an end. From then on, no Turk, Persian, Mongol, or Afghan ever set foot on the soil of Punjab except as a servant of the state or a friend. Ranjit Singh’s rule marked the beginning of a period of peace and prosperity.

According to tradition, some Sikh religious and social leaders urged Ranjit Singh to crown himself after occupying Lahore. During the Mughal regime, Lahore had served as the capital of Punjab and held great political significance. Although Lahore was under the control of the Bhangi *misl*, misgovernance led prominent citizens to invite Ranjit Singh to take over. The city was occupied without bloodshed, and Ranjit Singh issued strict orders to his troops to refrain from harming anyone. He ensured that people of all religious communities enjoyed complete religious freedom and social security.

It is said that it was particularly on the insistence of Baba Sahib Singh Bedi—a direct descendant of Guru Nanak and a highly respected figure in Sikh religious circles—that Ranjit Singh reluctantly agreed to the coronation. He had initially hesitated, fearing it would aggravate the jealousy of other Sikh chiefs. Just months earlier, the Ramgarhia and Bhangi chiefs had united at Bhasin to drive Ranjit Singh out of Lahore. In this context, Baba Sahib Singh Bedi offered to anoint Ranjit Singh as Maharaja. While some scholars question the authenticity of this account, it is a fact that Ranjit Singh’s territories were surrounded by a ring of independent powers, none of which were friendly toward the Sikhs or shared their political aspirations.

To the west and south, the Khalsa dominion was encircled by Muslim principalities stretching from Jhelum through Shahpur, Sahiwal, Jhang, Pakpattan, and ending at Kasur, near Lahore. Beyond them were the states of Kashmir, Hazara, Peshawar, Bannu, Dera Ismail Khan, Dera Ghazi Khan, Multan, and Bahawalpur. To the east, the British had advanced to Delhi, and in the north, Rajput chiefs were entrenched in hill states from Jammu to Kangra. Ranjit Singh was thus sandwiched between hostile forces and may have felt politically insecure, though the position of other Sikh confederacies was no better.

Another reason for Ranjit Singh’s hesitation may have been his own spiritual humility. He was not an orthodox Sikh and, like many rulers, had personal flaws. However, he held deep faith in the Gurus and their teachings. He feared that assuming the title of Maharaja might be perceived as a violation of Sikh principles of spiritual unity and egalitarianism. Therefore, even after being anointed Maharaja, he preferred to be addressed as “Bhai Sahib” or “Singh Sahib.” It is also reported that when he later named his son Kharak Singh as his heir, his general Hari Singh Nalwa protested, arguing that Ranjit Singh, as a trustee of Sikh rule, had no right to nominate a successor.

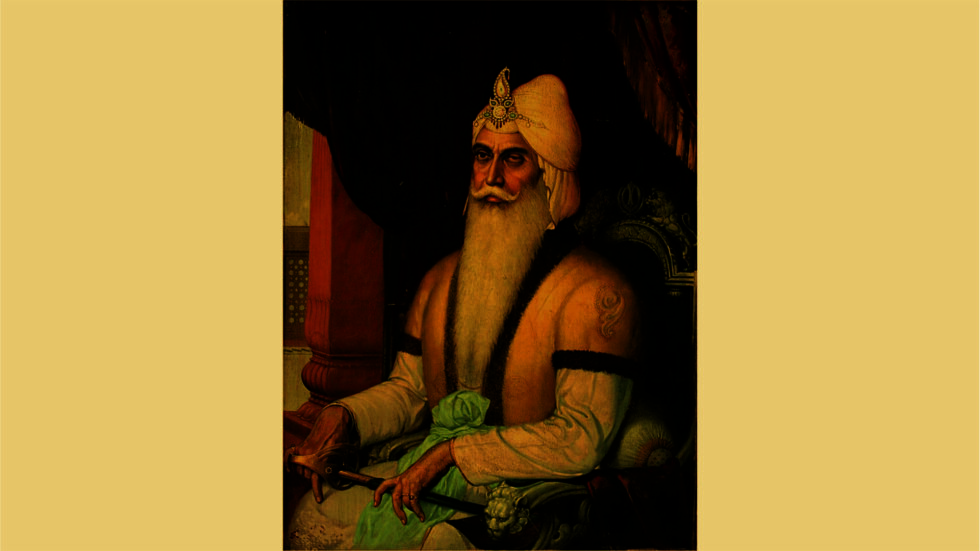

Ranjit Singh realized that the only way to ensure the Sikh community’s survival and prosperity was to unify the small chiefdoms into a strong, centralized Khalsa kingdom. For his coronation, the capital city of Lahore was decorated like a bride. A royal durbar was held inside the Lahore Fort. However, the ceremony itself was modest. He did not order canopies or crowns but allowed Baba Sahib Singh Bedi to mark his forehead with saffron. After the investiture, a royal salute was fired, and the young Maharaja paraded on elephant-back through jubilant crowds who were showered with gold and silver coins. In the evening, the city was illuminated with oil lamps and vibrant fireworks.

Dignitaries from Lahore and Amritsar of all communities attended the ceremony. Observers from Shah Zaman and the British Governor-General were also present: Diwan Ram Dayal represented the former, and Yusuf Ali Khan the latter. Ranjit Singh deliberately delayed their return to coincide with the coronation—a decision that reflected his political acumen. However, he derived his authority not from any foreign power but from the mystic entity of the Khalsa Panth. He acknowledged no earthly superior and always referred to his rule as the rule of the Khalsa.

Though solemn and significant, the ceremony reflected Ranjit Singh’s humility. He claimed no royalty for himself, wore no crown, and sat on no throne. He considered himself one of the people, a major departure from traditional monarchies, where rulers kept themselves aloof from the masses. He wanted to be called “Sarkar” or “Singh Sahib”, not “Maharaja.”

On the occasion, he distributed robes of honour to his nobles and gave generously to the poor. New coins were minted to commemorate the event. Poets composed verses to be inscribed on them. However, Ranjit Singh refused to have his image or name on the coins. Instead, they were struck in the name of Guru Nanak. His government was not a personal affair—it was the *Khalsa Sarkar*, and his court was known as the *Khalsa Durbar*. His currency, the Nanakshahi rupee, contained nearly a *tola* of pure silver. His gold *mohur* weighed 16.7 grams. All the coins minted that day were distributed in charity.

After the coronation, Ranjit Singh prioritized peace and governance. He reformed the administration of Lahore, established *panchayats* in villages, and ensured justice. Muslims were allowed to follow Islamic law. Qazis and magistrates, paid from the state treasury, were appointed, including Nizam-ud-Din as Qazi and Muhammad Shahpuri and Saadullah Chishti as Muftis. A hospital and chain of dispensaries were opened under Hakim Nur-ud-Din. Medicine was free. One lakh rupees were allocated for building a new wall around Lahore. Police posts were established, and Iman Bakhsh was appointed Kotwal of the city. Ranjit Singh also supported schools, mosques, and temples. Though he made no changes to the existing Mughal agricultural and land revenue systems, his administration assured peace and justice after many years of turmoil.

In 1803, during a visit to Amritsar, Ranjit Singh held a military durbar and conferred honours on his generals. Desa Singh Majithia received command of 400 cavalry; Hari Singh Nalwa, 800 infantry and cavalry; Hukma Singh Chimni was made superintendent of light artillery with 200 cavalry; Ghause Khan was placed in charge of heavy artillery with command over 2,000 cavalry.

Ranjit Singh’s coronation thus marked not just the rise of a sovereign but the foundation of a just and inclusive Khalsa rule in Punjab.

Dr. Dharam Singh