The Babbar Akali Movement forms a very important part of the history of Punjab as well as of the Sikhs. The contributions and sacrifices of the Sikhs during the freedom movement against British rule occupy a foremost place. Several significant movements emerged from Punjab, including the Gurdwara Reform Movement and the Babbar Akali Movement (which were largely religious in nature), the Ghadar Movement (initiated by Indian migrants returning from the U.S.A. and Canada after the First World War), the Kirti Kisan Movement, and the Hindustan Republican Army led by S. Bhagat Singh, Chandra Shekhar Azad, and others. All played crucial roles in awakening national consciousness and accelerating the fight for independence.

While some of these movements, such as the Akali Movement, followed non-violent methods, the Babbar Akali Movement embraced militant action, believing force was necessary to achieve freedom. Born as an offshoot of the Akali Movement, the Babbar Akali Movement was fueled by the growing resentment of Sikhs toward British rule. Their anger stemmed from the annexation of Punjab, the suppression of the Kuka Movement, the deportation of Sardar Ajit Singh for opposing unjust water taxes in canal colonies, the mistreatment of the passengers of the Komagata Maru, and British interference in Sikh religious affairs by supporting corrupt Mahants and obstructing the Gurdwara Reform Movement.

Events such as the Nankana Sahib massacre and the atrocities during the Guru Ka Bagh Morcha (1921–22) further inflamed Sikh sentiment—especially among those from the Bist Doab (Jalandhar region). Many came forward to confront those they saw as enemies of the Gurdwara Reform Movement. The Babbar Akali Movement emerged as a radical response—a militant extension of the peaceful Akali agitation aimed at liberating Sikh shrines from the control of self-serving priests.

While the mainstream Akali leadership advocated non-violence, a faction rejected this passive approach. Inspired by the martial tradition of Guru Gobind Singh, they embraced the philosophy: “When all other means have failed, it is lawful to take up arms.” Leaders such as Kishan Singh Gargaj, Karam Singh Babbar, and Nand Singh Ghurial expressed this militant zeal in their writings and speeches. They made fiery, seditious proclamations and took to underground life as “Chakarvartis” (wandering revolutionaries), targeting British officials, traitorous Indian informers, and corrupt Mahants.

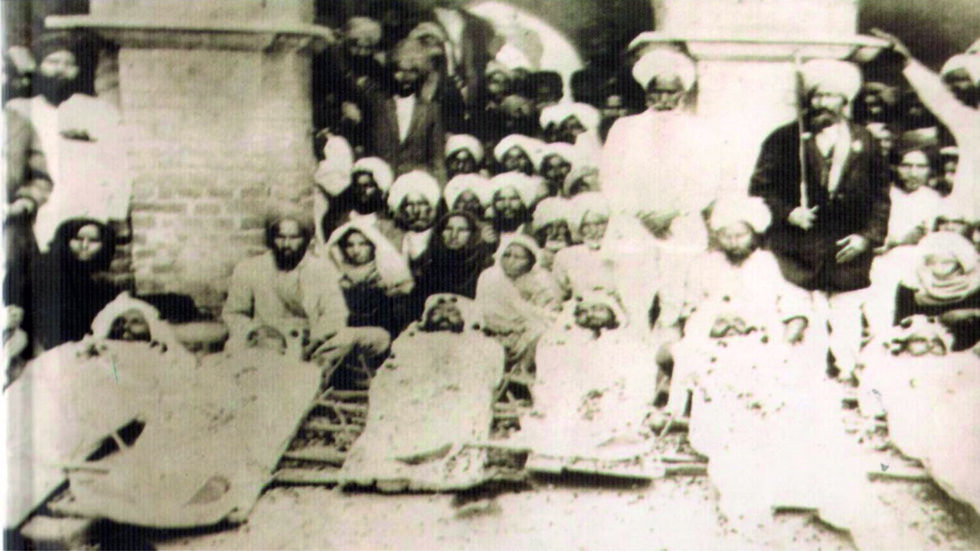

The movement gained traction during the Sikh Educational Conference in Hoshiarpur (March 25–27, 1921), where radicals like Master Mota Singh and Kishan Singh Gargaj, a retired Havildar Major from the Indian Army, convened in secret. They plotted to avenge the killings at Nankana Sahib and drew up a list of British officials. However, many were arrested on May 23, 1921. While Master Mota Singh and Kishan Singh escaped arrest, the latter soon formed a secret group called the Chakarvarti Jatha, organizing soldiers and farmers against British rule.

Later, Karam Singh of Daulatpur created a similar militant band in Hoshiarpur. In August 1922, these groups merged into a single organization named the Babbar Akali Jatha, headquartered in Rajowal (District Hoshiarpur), under the spiritual patronage of Sant Thakur Singh. Kishan Singh Gargaj was elected Jathedar (President), with Dalip Singh Gossal, Karam Singh Jhingan, and Baba Santa Singh serving as key office bearers. The organization began publishing literature, including the newspaper Babbar Akali Doaba, to spread their message.

The Babbar Akalis made concerted efforts to recruit soldiers, students, and civilians. Their December 25, 1922 resolution marked a strategic shift to directly target British collaborators—“jholichucks” (toadies or informers). Leaders like Karam Singh Daulatpur and Bhai Udey Singh organized squads to punish such individuals. At the time, the distinction between peaceful Akalis and militant Babbar Akalis was still blurred, but the Babbars’ violent tactics made them a separate force. Although the committed core of Babbar Akalis never exceeded 500 members, they had a wide network of sympathizers who provided food, shelter, and logistical support.

To maintain secrecy, the Babbars adopted codes similar to those used by Sikh warriors during their 18th-century resistance against Mughal persecution. They followed a policy of direct confrontation—every member was expected to assassinate a collaborator, and betrayal was punishable by death.

The movement reached its height between mid-1922 and late 1923. Several British officers and informers were killed. In response, the British government took stern measures. Proclamations announcing rewards for capturing Babbar Akalis were issued on November 30, 1922, April 25, 1923, and August 3, 1923. Despite arrests, the Babbars continued their campaign. British MPs raised the issue in Parliament, with figures like Sir Charles Yates, Colonel Howard, and Hope Simpson criticizing the government’s failure to suppress the rebels.

Eventually, the government responded with a strong crackdown. Military units were stationed in sensitive areas, and joint military-police operations were launched. Leaflets were dropped from aircraft to demoralize sympathizers, and punitive taxes were imposed on villages. Yet, the Babbar Akalis remained defiant.

One of the major clashes occurred at Babeli (August 31, 1923) where Karam Singh (Editor), Udey Singh, Bishan Singh, and Mohinder Singh were killed after being betrayed. The Mannanhana encounter (October 25, 1923) saw Dhanna Singh Behbalpur kill nine policemen with a grenade, including A.F. Harton and W.H.P. Jenkins, before dying himself. The final encounter happened in Lyallpur (June 8, 1924) where Waryam Singh Dhugga was shot dead. After this, the movement rapidly declined.

The Babbar Akali Conspiracy Cases

Following these events, a large number of Babbars were arrested and tried. In the main conspiracy case, six individuals—Kishan Singh Gargaj, Nand Singh Ghurial, Dalipa Dhamian, Karam Singh Haripur, Santa Singh Chhoti Herion, and Dharam Singh Hayatpur—were executed on February 27, 1926. In the supplementary case, six more—Banta Singh Gurusar Satlani, Gujjar Singh Dhapai, Mukand Singh Jassowal, Nikka Singh Gill, and Sunder Singh Lohke—were hanged on February 27, 1927.

Though the Babbar Akali Jathas ceased to exist, their influence persisted.

⸻

Legacy and Impact

The Babbar Akali Movement made a profound impact on:

• The Gurdwara Reform Movement: Their sacrifices forced the British to negotiate with the SGPC in 1923 and 1925.

• Other revolutionary groups: The Naujawan Bharat Sabha, Kirti Kisan Party, and later revolutionaries like Bhagat Singh were inspired by their tactics and ideals.

• Individuals like Udham Singh, who assassinated Sir Michael O’Dwyer in 1940, were influenced by the Babbar Akalis’ fierce nationalism.

• Panjab’s nationalist psyche and Sikh political consciousness.

Even though the movement was short-lived, the Babbar Akalis’ courage, martyrdom, and commitment to justice became a symbol of militant resistance against colonial rule. Their story remains an unforgettable chapter in India’s freedom struggle and Sikh history.

Dr. Gurcharan Singh Aulakh